How the Body Absorbs Sugar - High Fructose Corn Syrup

Nutrition, July 16, 2016

Fructose is absorbed by the body differently than other sugars, and it does not register in the body metabolically in the same way that glucose does. For example, consumption of glucose triggers a cascade of biochemical reactions by increasing insulin release from the pancreas, enabling sugar in the blood to be transported into cells, where it can be used for energy.

Glucose also increases the production of leptin, a hormone that helps regulate appetite and fat storage, and it suppresses another hormone produced by the stomach called ghrelin that helps to regulate food intake. It has been suggested that when ghrelin levels drop after a carbohydrate meal (containing glucose), hunger declines.

However, fructose seems to behave more like fat with respect to the hormones involved in regulation of body weight. Fructose does not stimulate insulin secretion, increase leptin production or suppress production of ghrelin. This suggests that consuming a lot of fructose, like consuming too much fat, could contribute to weight gain.

Another concern is the effect of fructose on the liver, where it is converted into the chemical backbone of triglycerides more efficiently than glucose is. Triglycerides, which are found in low-density lipoproteins (LDL), the most damaging form of cholesterol, have been linked to an increased risk of heart disease. It has been shown that fructose produces significantly higher plasma triglyceride levels than does glucose in male test subjects.

These scientists who performed this research concluded that diets high in added fructose may be undesirable, particularly for men, and that glucose may be a suitable sugar replacement1. Other research suggests that fructose may alter magnesium levels in the body, which could in turn accelerate bone loss according to a USDA study published in 2000 in the Journal of the American College of Nutrition.

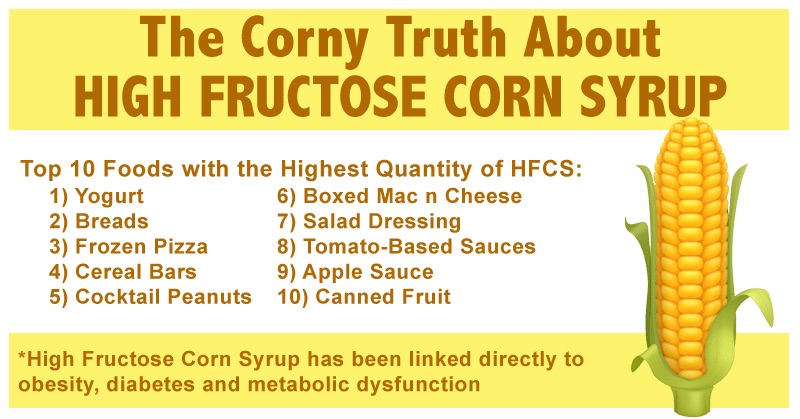

Elliot., et al.2 examined evidence from multiple studies as to whether fructose consumption might be a contributing factor to the development of obesity and the accompanying metabolic consequences observed in insulin resistance syndrome. They concluded that large quantities of fructose from a variety of sources, including table sugar and high-fructose corn syrup, induce insulin resistance, impair glucose tolerance, produce high levels of insulin, elevate a dangerous type of fat in the blood and can cause high blood pressure in animals.

However, these researchers also state that although energy intake, body weight and adiposity all increase in animals, less information is available in humans. And a barrage of more recent studies has seriously undermined the proposed HFCS-obesity link. A special supplemental issue of the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition contained five studies that concluded that HFCS is no better or worse than table sugar in terms of causing weight gain.

HFCS and Athletes

Athletes should be aware of the following facts. First, added fructose in the forms of sucrose and high-fructose corn syrup does not appear to be the optimal source of carbohydrate in the diet. Secondly, the concerns that have been raised about the addition of fructose to the diet as sucrose or high-fructose corn syrup should not be extended to naturally occurring fructose obtained from fruits and vegetables.

It is worth mentioning that many of the studies examining the effects of fructose use pure fructose rather than the combination of fructose and glucose found in corn syrup. It is also worth pointing out that there is no single reason for the obesity epidemic or the onslaught of diabetes in America. What does appear to play a major role though is a lack of physical exercise.

With regard to the specific issue of the use of HFCS in ergogenic aids such as sports drinks, research suggests that it is not problematic and may even be beneficial. Studies by Asker Jeukendrup and colleagues at the University of Birmingham have shown that carbohydrates are absorbed and metabolized at a faster rate in sports drinks containing glucose and fructose than in sports drinks containing glucose alone, resulting in superior endurance performance.

The reason appears to be that because the two sugars are processed through different pathways, they can be processed simultaneously. In any event, sugars of any kind in sports drinks are extremely unlikely to contribute to weight gain if consumed during workouts, as these sugars are used immediately to fuel muscle contractions.